China's transition from managing water contamination issues to rehabilitating natural habitats

In recent years, China has taken significant strides in improving its water quality, but the country continues to grapple with persistent issues, particularly in rural areas.

In 2021, China published a plan aimed at having 40% of village wastewater pass through treatment plants by the end of 2025. This is part of a broader effort to address water pollution, which has been a long-standing concern in the country.

The State Council issued a systematic plan in 2022 for dealing with new pollutants, focusing on monitoring, industry assessment, and a treatment strategy focusing on risk prevention. This plan was a response to China's announcement in 2022 of a campaign to tackle new pollutants such as persistent organic pollutants, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and antibiotics.

However, agriculture remains a significant source of these pollutants. The Leishui River in southern Hunan was found to have abnormal levels of thallium pollution in late March, an uncommon pollutant that causes both acute and chronic poisoning. Despite this incident, there have been no reports of harm to health due to the thallium pollution.

Agricultural pollution is more dispersed than that from industry and cities, making it harder to identify, monitor, and track sources of pollution. Experts suggest that copying the approaches used in cities and industry will be ineffective for the dispersed and changeable patterns of pollution in rural areas.

He Linghui, a notable figure in water management, has suggested expanding the list of regulated pollutants over time, with emissions standards and overall caps to reduce usage. Luo Wushan, on the other hand, thinks in situ recycling should be explored: using the restoration and creation of river and lake ecologies to increase the water's ability to clean itself.

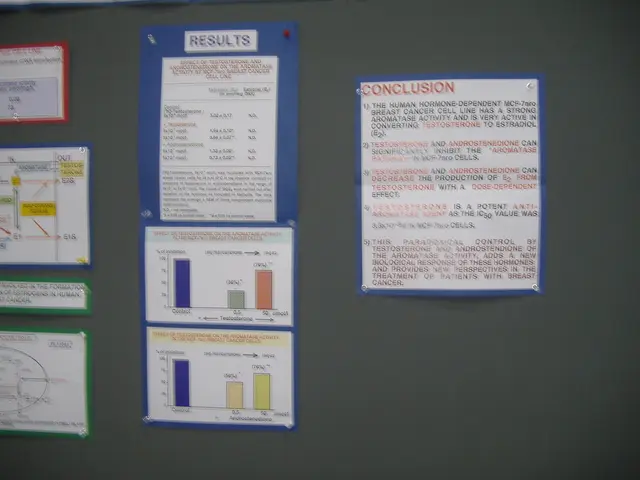

China's efforts to improve water quality have shown promising results. Between 2014 and 2024, the percentage of surface water suitable for drinking, fishing, and direct human contact rose from 63% to 90.4%. The share of the most polluted waters fell from 9.2% to 0.6% during the same period.

The country's water-monitoring network got a boost in 2015 with the State Council's Water Pollution Action Plan. The Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People's Republic of China launched an online platform in 2016 as part of the fight against water pollution, where they regularly publish data on water quality and pollution levels.

China has also identified over 3,000 "foul waterways" through a combination of public reports, real-time monitoring, and remote sensing. In 2024, 98% of all urban wastewater was treated compared to only 45% of rural domestic wastewater.

However, challenges remain. Over 20% of groundwater was deemed to be Class V (too polluted to drink) between 2021 and 2024. Agriculture is a significant source of antibiotics in China's surface water and even groundwater. In the Yangtze River basin, 1,600 tonnes of antibiotics reached the water and other environments every year between 2013 and 2021.

Recently, China has been exploring a shift from a focus on preventing pollution alone to management of ecosystems for rural areas. Luo Wushan, for instance, believes that poor water quality in rivers and lakes is mainly caused by phosphorous levels, with 99% coming from agriculture.

As China continues to address its water pollution issues, it is clear that a multi-faceted approach will be necessary to achieve lasting improvements. This includes expanding regulations, exploring new recycling methods, improving wastewater treatment, and addressing the unique challenges posed by agricultural pollution.