Ice Bending Generates Electricity, Potentially Shedding Light on the Origin of Lightning

In a groundbreaking study, published in the prestigious journal Nature Physics, a team of researchers from the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2) have discovered that ice generates electricity when bent. This finding not only challenges our understanding of ice but also brings it on par with electroceramic materials such as titanium dioxide.

Common ice, known as hexagonal ice - Ih, is not piezoelectric. However, the researchers suggest that our understanding of ice is incomplete due to the continued discovery of new phases and anomalous properties. The lack of piezoelectricity in common ice, they explain, is due to the geometric frustration introduced by the Bernal-Fowler rules.

The Bernal-Fowler rules state that two hydrogen protons must be adjacent to each oxygen atom, but there can only be one hydrogen proton between two oxygen atoms in hexagonal ice. This arrangement results in hexagonal ice not exhibiting long-range order in its hydrogen atoms, leading to randomly oriented water dipoles and no macroscopic piezoelectricity.

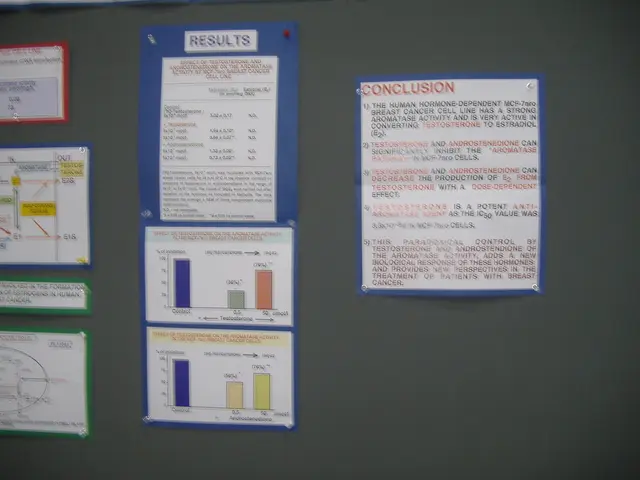

However, the team found that a thin 'ferroelectric' layer at the surface of ice forms at temperatures below -113 °C. This layer is responsible for the generation of electricity when ice is bent, a phenomenon known as the flexoelectric effect.

The importance of water and ice to life and the Earth's climate has led to extensive study. The new discovery has significant implications, as it provides a new explanation for how charge builds up in clouds and produces lightning. The results of the experiments match those observed in ice-particle collisions in thunderstorms.

The team plans to continue research into the effect, including the potential for producing new electronic devices using ice as an active material. The study was conducted by the "CAMP (Cloud and Aerosol Measurement and Process) research group," who have provided new insights into how electrical charge forms in clouds.

Water ice is one of the most widespread solids on Earth, and this new discovery could lead to a better understanding of its behaviour and properties. As we continue to explore and learn more about ice, it is clear that there is still much to discover.