Protecting Canada's Grizzlies through Indigenous Wisdom

In the heart of British Columbia, Canada, lies one of Earth's largest remaining temperate rainforests - the Great Bear Rainforest. This vast expanse is not just a haven for diverse flora and fauna, but also a cultural and historical treasure trove for the coastal First Nations who have lived along its shores for centuries.

A recent genetic study, spearheaded by five coastal First Nations and scientists at the University of Victoria, has shed new light on the grizzly bears that inhabit this region. The study revealed three distinct genetic groups of grizzly bears, aligning with the traditional territories of three Indigenous language groups: Tsimshian, Northern Wakashan, and Salishan Nuxalk.

This groundbreaking research challenges the effectiveness of current government grizzly bear management practices, which often overlook genetic data. The findings could potentially lead to a richer wildlife watching experience for travelers at places such as Indigenous-owned Knight Inlet Lodge on Vancouver Island.

The understanding that First Nations societies have gained over centuries allows for a holistic approach to ecosystem management. Instead of managing resources on a regional scale, they adopt a watershed approach, considering the interconnectedness of all life within the ecosystem.

Indigenous-led or sponsored research has already impacted bear conservation policy in British Columbia. In 2017, trophy hunting was ended, and habitat on B.C.’s islands was protected. The Commercial Bear Viewing Association of British Columbia (CBVA) sets the standard for responsible bear viewing in the Great Bear Rainforest and played a significant role in ending trophy hunting.

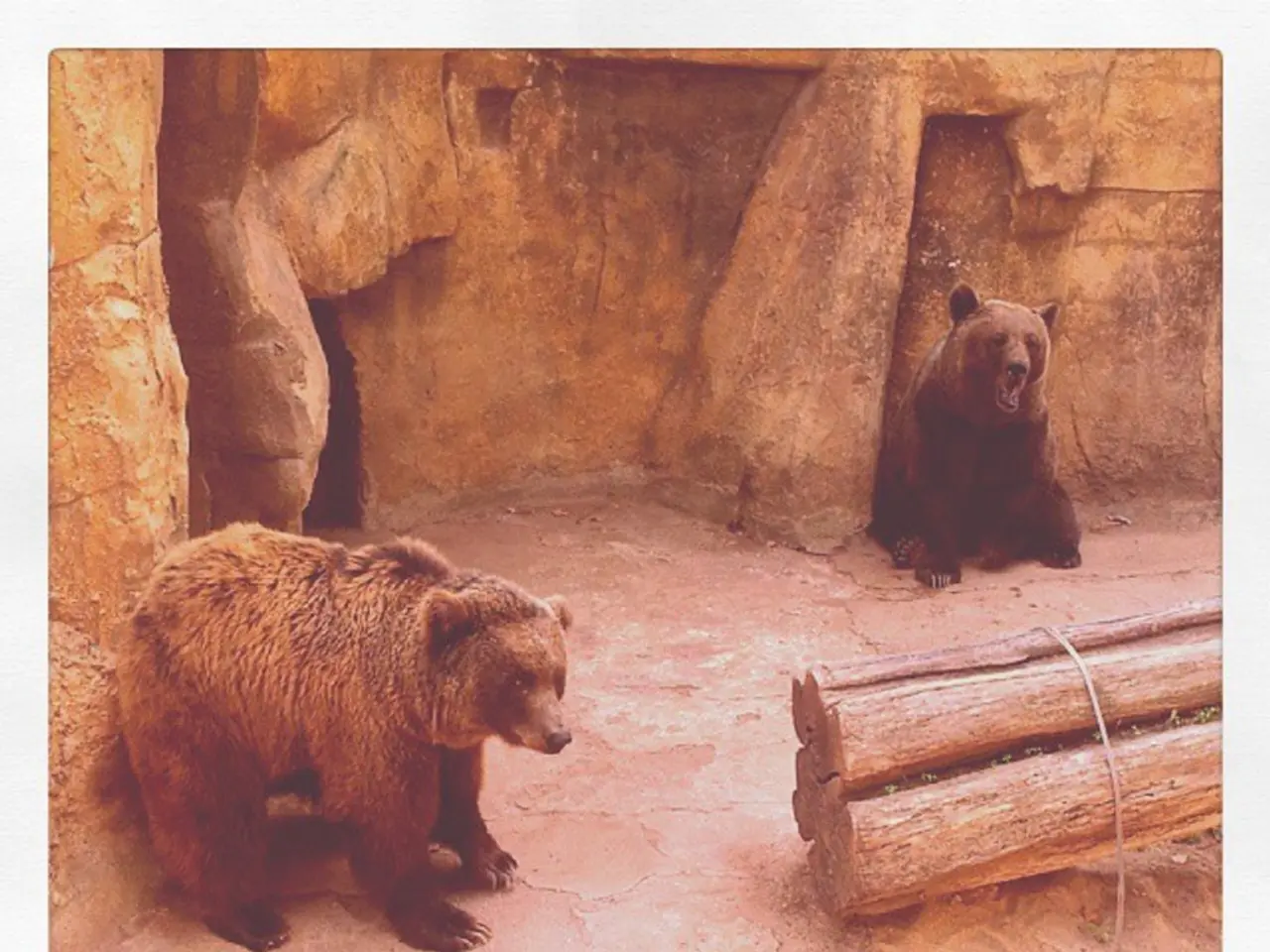

Coastal Indigenous peoples have a deep connection with grizzly bears, viewing them more as kin than a source of fear. A study by the Wuikinuxv Nation and the Raincoast Conservation Foundation found that people and bears can share salmon equitably in a way that benefits both species.

The First Nations groups involved in the 2021 genetic study include the Kitasoo/Xai'Xais and Gitga'at Nations. Indigenous ecological knowledge has been shown to contribute to more nuanced research and lead to more successful conservation efforts, both in British Columbia and around the world.

Kate Field, a conservation scientist at the University of Victoria, is collaborating with Indigenous researchers to study the effects of human presence on bear behavior. Meanwhile, bear guides like Ellie Lamb, a guide at CBVA partner Tweedsmuir Park Lodge, are continually improving their knowledge about grizzly bears from bear behavior experts and the Nuxalk people.

For those seeking to explore the Great Bear Rainforest, Chloe Berge offers hiking opportunities through Indigenous Tourism BC's website. First Nations knowledge about coexisting with bears is invaluable, and guides can learn from them, ensuring a respectful and enriching experience for both travelers and the bears they encounter.

In the Great Bear Rainforest, the cultural significance of grizzlies to coastal First Nations offers travelers a unique opportunity to reconsider their own relationship with grizzly bears and the land. Monitoring for genetic differences can help improve the health of a grizzly bear population by alerting managers to high levels of inbreeding and helping bears adapt to threats and a changing ecosystem. As we continue to learn from the Indigenous communities who have lived in harmony with these magnificent creatures for millennia, we can work towards a future where both humans and grizzlies thrive.